Recently, currencies in some Asian countries and regions have depreciated against the US dollar to varying degrees.

What were the specific causes of the 1997 Asian financial crisis?

Is the world economic pattern the same as it was more than 20 years ago?

Will the former Asian dragons and tigers repeat the mistakes of history?

Is the present moment similar to that past moment?

Today, the president will delve into this topic in detail.

This is the Financial One-on-One Society.

In 1997, during the Asian financial crisis, the countries most severely affected were Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, and South Korea.

Additionally, Singapore, our Hong Kong, and Taiwan also suffered significant impacts.

Can you see from this list of affected areas that these eight places were precisely the most rapidly developing Asian Four Little Dragons and Four Little Tigers at that time.

Before the financial crisis, over the course of 20 years, Asian countries and regions created a miracle of world economic growth.

At that time, the economies of Taiwan, China, Hong Kong, China, Singapore, and South Korea grew the most rapidly and were dubbed the "Asian Four Little Dragons."

In addition, some other Asian countries and regions, such as Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia, also achieved rapid economic growth, and these four countries were called the "Four Little Tigers."

People referred to the economic growth miracle of this period in Asia as the East Asian model.

However, the leader driving the "East Asian model" was not among these eight places but Japan.

After World War II, Japan was the first country in Asia to rise and achieve industrialization.

In 1960, Japan was the first in Asia to complete industrialization.

Japan's heavy industry, automobile manufacturing, electronic products, and other industries developed rapidly and gradually gained an advantageous position in the international market.

However, as the country completed industrialization, its labor costs also continued to rise.

Japan gradually began to transfer some low-end manufacturing to other regions in Asia.

The Japanese economist Akamatsu Kiyoshi proposed the "Flying Geese Model" of Japan's industrial development in 1962.

As the name suggests, the Flying Geese Model is like a formation of geese, with several major economies in East and Southeast Asia arranged in a goose formation.

Japan, being the most developed economy in Asia at the time, said, "I will form the head and lead you to fly."

Japan's industrial chain was transferred according to this Flying Geese Model.

High-end industries were retained, lower-end ones were transferred to the Four Little Dragons, and even lower-end ones were transferred to the Four Little Tigers.

Concurrently with the industrial chain transfer, Japan also increased its investment scale in these countries and regions.

Under Japan's leadership, the entire East Asian economy entered the fast track of development, which is the economic growth miracle of the "East Asian model."

In 1985, a significant historical event occurred, which, like a stimulant, accelerated the advancement of Japan's Flying Geese Model.

It was the year when the United States and Japan signed the Plaza Accord.

You might say that the Plaza Accord was not aimed at Japan, so how did it also affect other regions?

I will discuss the specific content of the Plaza Accord in this video in detail.

Let me briefly mention the result here.

In the two years after the Plaza Accord was signed, the yen appreciated against the US dollar by a factor of two.

The most affected by the appreciation of the domestic currency is the export.

With the yen appreciating by a factor of two, Japanese goods exported to the United States were equivalent to a price increase by a factor of two.

This was a devastating blow to Japanese export enterprises.

However, Japan also immediately took countermeasures.

When the export of the motherland is affected, I will let the enterprises go overseas, and if they are not priced in yen, they will not be subject to the Plaza Accord, right?

At this time, the Flying Geese Model came in handy.

Japanese enterprises began to accelerate the transfer to the aforementioned Little Dragons and Little Tigers.

It used to be only low-end industry output, but now even Japan's automobile industry began to transfer.

For example, many Japanese car companies invested heavily in factories in Thailand, once turning Thailand into the "Detroit of Asia."

In addition, the appreciation of the yen also had benefits, that is, the cost of yen for overseas investment became lower.

Originally, 1 yen could buy a jackfruit in Thailand, and after appreciating by a factor of two, 1 yen could buy two jackfruits.

As a result, Japan's foreign investment became even more crazy.

By 1990, Japan's foreign investment in Asia had surged by a full six times.

In fact, the 10 years that Japan lost was precisely the 10 years of expansion of Japan's overseas capital.

Looking at the Little Dragons and Little Tigers, under the simultaneous crazy investment of industry and capital, the economy was like a rocket takeoff.

During this period, Hong Kong's annual GDP growth was between 5% and 7%, gradually consolidating its position as an international financial center in Asia.

Taiwan's GDP reached 7-9%, and the electronic information industry developed.

Thailand's GDP growth rate was also as high as about 9%, and foreign capital inflow was also greater.

South Korea's growth during this period was particularly significant, with an average annual growth rate often exceeding 9%.

South Korea's heavy industry and technology industry expanded significantly during this period.

The entire Asian economy was thriving.

But at this time, the leader of the Flying Geese Model had an accident.

Japan, due to the sharp appreciation of the yen, attracted a large amount of international hot money into Japan's domestic stock market and real estate, blowing up an unprecedented economic bubble.

In 1991, this bubble was suddenly burst.

The assets plummeted, and the country experienced severe deflation.

The Bank of Japan's response was to lower the interest rate to an ultra-low level close to 0.

At the same time, other countries on the Flying Geese Model were still keeping their economies hot, and domestic interest rates remained high.

For example, Thailand's interest rate during this period was around 10%.

Japan was 0, and Thailand was 10%, such a large interest rate difference, which led to arbitrage transactions.

During this period, a group of arbitrageurs known as "Mrs. Watanabe" appeared in Japan, which I have done a special issue on before.

Western international speculators also began to circle around.

Speculators such as Soros's Quantum Fund, Julian's Tiger Fund, Morgan Stanley, and others were drooling over Asia.

With the rise of arbitrage transactions, a large amount of capital began to flow into Asian countries and regions.

But this money was completely different from before.

At the beginning of the Flying Geese Model, it was a model of industrial input plus supporting capital, and the money that flowed in was to serve the real industry, to buy land and build factories, to purchase equipment, to expand operations, and to obtain stable industrial returns.

This is a positive economic development model.

However, when international speculators came in to engage in arbitrage transactions, they were usually short-term behaviors, making a quick profit and then running away.

The influx of these hot money not only made arbitrage.

There is an old Chinese saying: "Come on in."

They will also take the opportunity to inject capital into the stock market and real estate, blowing the economic bubble of the Little Dragons and Little Tigers bigger and bigger.

Let me explain by the way.

1.

Foreign capital entering these countries for long-term investment, such as setting up factories, participating in infrastructure construction, etc., is a relatively healthy investment.

2.

The so-called short-term hot money.

Hot money is an important concept in economics, especially when we study economic cycle fluctuations and economic crises, we often use this concept.

Generally, investments that are short-term, less than one year, and come in and out quickly are called hot money.

Due to the high economic growth rate of these Asian countries and regions, the price of real estate and the stock market rose quickly, so many foreign funds entered these countries and regions to speculate, hoping to make a quick profit and get in and out quickly.

Before the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the inflow of hot money in these Asian countries and regions was very huge.

3.

Foreign debt.

The foreign debt borrowed by the enterprises and financial institutions of these countries and regions also grew rapidly year by year before the 97 crisis.

For example, from 1990 to 1995, Thailand's net capital inflow increased by 126%, and Thailand's foreign debt also exceeded 100 billion US dollars, accounting for 60% of GDP.

Indonesia's situation is basically the same, and the housing prices in the main cities of these countries have risen by more than 200% in five years.

I will talk about the dangers of foreign debt later.

During this period, the Asian economies did not understand that the sharp fluctuation of the yen against the US dollar was gradually devouring them.

Many views will attribute the culprit of the Asian financial crisis to the capital plundering of international speculators such as Soros.

But in fact, the success of speculators is just a result, and the fundamental reason is that there were serious loopholes in the Asian economic system.

These speculators formally smelled the opportunities in the loopholes and dared to stir up trouble.

This loophole is that the development model of the Asian economy adopted: one industrial chain, two currency standards.

One industrial chain is the goose model exported by Japan mentioned earlier.

Two currency standards refer to, first, the currencies of the Asian economies generally adopt the method of pegging to the US dollar exchange rate.

In global trade, the US dollar is the international leading currency, and the world's purchases are basically priced and settled in US dollars.

For cross-border trade, pegging to the US dollar is a relatively secure way, which is the first currency standard adopted by the Asian economies.

But at the same time, the capital inflow in Asia mainly comes from Japan, so the yen has become the main currency of capital inflow.

The yen has become the second currency standard.

At that time, when the world's two largest economies, the United States and Japan, began to have trade friction, the exchange rate between the US dollar and the yen fluctuated sharply.

These small economies had to suffer.

When the boss and the second boss fight, why are the surrounding little brothers injured?

As mentioned earlier, after 1985, the yen began to appreciate against the US dollar, and Japan began to increase investment in Asia.

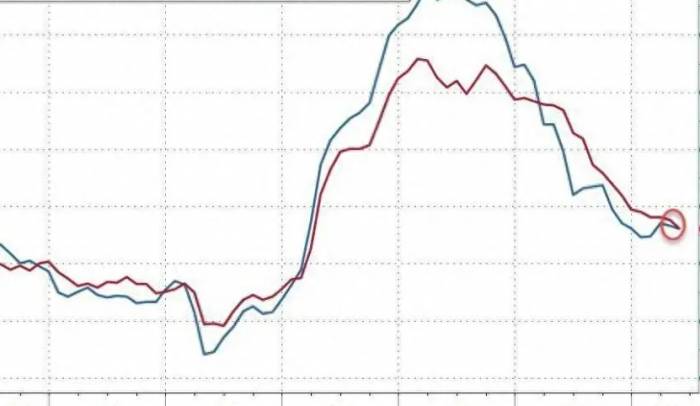

But by 1995, the situation reversed.

After the yen reached a peak of 80:1 against the US dollar, it began to fall.

By 1998, the yen depreciated to 130:1 against the US dollar.

The depreciation of the yen led to a reversal of Japan's investment trend.

A large amount of investment began to withdraw from Asia.

From 1995 to 1999, during this period, Japanese banks withdrew a total of 235.2 billion US dollars from the Little Dragons and Little Tigers, accounting for 10% of these economies' GDP.

Such a huge amount of capital was withdrawn, equivalent to drawing 1/10 of the blood from a normal person's body, and even an iron man could not stand such a blow.Even so, the Little Dragons and Little Tigers still clung stubbornly to the US dollar.

They failed to understand at the time that this would plunge them into a predicament from which they could not recover, and it also provided international speculators with an opportunity to exploit.

Let's take Thailand, the country hardest hit by the crisis, as an example.

The Bank of Thailand has always claimed that the baht's exchange rate was pegged to a basket of currencies, but what was in that basket was never clearly stated.

It was only after the fact that the public learned that since 1984, the exchange rate between the baht and the US dollar had been consistently stable at 25:1.

After Soros successfully attacked the British pound in 1992 and emerged victorious, he discovered the fatal flaw in economies that had a "soft peg" to the US dollar.

Thus, the "soft peg" became the target of speculators.

Finally, in 1997, international speculators discovered the Achilles' heel of Asia and began to heavily short sell.

Let's briefly discuss how speculators can profit from short selling a country's currency.

For instance, in '97, the exchange rate between the baht and the US dollar started at 25:1.

At that time, Soros borrowed 100 million baht and then sold it, which could be exchanged for 4 million US dollars.

When the baht began to depreciate against the US dollar, from 25:1 to 50:1, Soros only needed to use 2 million US dollars to exchange for 100 million baht, and then close his position for a profit.

Of course, there are some transaction costs involved.

After deducting these costs, that's Soros' net profit.

This profit is no longer just windfall; it's practically highway robbery.

In reality, the baht did depreciate by more than half in 1998.

So the question arises, how could Soros be so certain that the baht would depreciate?

If he had bet wrong, wouldn't that be a huge loss?

Because Thailand, like other economies, could not escape a "trilemma" in the modern financial system known as the Mundell-Fleming Impossible Trinity.

It means that a country's monetary policy independence, fixed exchange rate, and free capital mobility cannot be achieved simultaneously.

At most, you can choose 2 out of 3.

Monetary policy independence means that whether the domestic currency is loose or tight is decided by oneself, without being influenced by other countries; a fixed exchange rate means that the exchange rate between the domestic currency and the target country's currency remains unchanged, which is beneficial for import and export trade; free capital mobility means no capital controls, and capital can flow in and out freely.

Why can't all three be satisfied at the same time?

Let's go back to Soros' attack on the baht, and you'll understand immediately.

At that time, Thailand chose to have a fixed exchange rate and free capital mobility, so its domestic monetary policy was no longer up to itself.

But at this point, a contradiction arose.

Due to previous foreign capital, such as the yen, which had very low interest rates and was very easy to borrow, a large number of enterprises and individuals began to take on a lot of foreign debt for development.

Foreign currency had to be exchanged for baht to be spent domestically, so the demand for baht increased, and there was a trend of exchange rate appreciation.

But Thailand also wanted to protect its exports - if the exchange rate was high, the price of your goods would be expensive for foreigners, so to balance the exchange rate, the Bank of Thailand had to print a lot of money, increase the supply of baht, and then buy yen in the foreign exchange market with baht, so that the exchange rate could remain stable.

In this way, more and more baht was printed, but the Bank of Thailand had to maintain this loose monetary policy.

As a result, the economic bubble in Thailand became more and more serious, and a large amount of capital flooded into the stock market and the real estate market.

It led to extremely high housing prices in Thailand and a surge in the stock market.

You see, the script of economic bubbles around the world is almost the same.

However, when the Japanese economic bubble burst and the yen began to depreciate, Japan's overseas investments began to flow back in large amounts, and the direction of buying and selling yen and baht was reversed.

You should know that at this time, there is a trend of depreciation of the baht's exchange rate.

Many enterprises in Thailand borrowed yen debt, and if the baht's exchange rate fell at this time, it would mean that their debt burden would increase.

At this time, the government still wanted to stabilize the exchange rate, so it could only use its foreign exchange reserves to buy baht.

Soros was precisely targeting this weakness of Thailand, as long as he depleted Thailand's foreign exchange reserves, the baht would definitely depreciate.

Soros and other international speculators began to accelerate the consumption of Thailand's foreign exchange reserves.

In May 1997, they began to sell off baht in large quantities, and the more they sold, the more the Thai government had to use its foreign exchange reserves to take in.

At the same time, there was also a fire in the backyard of Thailand.

Thai enterprises that had borrowed a large amount of foreign debt began to worry about the depreciation of the baht, because once the baht depreciated, the cost of corporate debt repayment would increase sharply.

So Thai enterprises also began to operate like speculators, and also began to sell off baht in large quantities.

In addition, the financial supervision in Thailand at that time was very unregulated, and a large number of private banks in Thailand did not follow the instructions of the central bank and transferred a large amount of capital away.

In this way, the supply of baht in the foreign exchange market was further in excess of demand.

On May 1, 1997, Thailand's foreign exchange reserves were 37.2 billion US dollars, but only two weeks later, it decreased by 21.7 billion US dollars.

By June 30, Thailand's foreign exchange reserves were only 2.8 billion, almost zero.

Thailand had to give up the fixed exchange rate, and the baht depreciated by 56% in one year.

International speculators won a complete victory.

Thailand was completely defeated in this currency defense war!

Since then, these speculators have copied the same method and attacked other Asian countries and regions such as the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, and South Korea.

A financial storm swept across Asia.

Today, the currencies of Asian economies have generally depreciated.

Will the storm of that year come back again?

The president thinks the possibility of the crisis coming back is very, very small.

Because now is different from the past.

Compared with 1997, the level of foreign debt in most Asian countries is relatively low, and the foreign exchange reserves are relatively sufficient, which provides a stronger buffer against external shocks.

Many Asian countries have adopted a more flexible floating exchange rate system after the 1997 financial crisis, which has increased the adaptability to external shocks.

Moreover, today, Asian countries have generally strengthened financial supervision and improved financial stability and risk resistance.

Now, Asian countries have strengthened economic cooperation and financial cooperation, such as through currency swap agreements and other measures, to enhance the regional financial security network.

The growth model of Asian economies is more diversified, reducing dependence on a single export-oriented economy.

At that time, Japan was the main capital exporting country in Asia, and the goose formation mode of Japan brought a system with one industrial chain and two currency standards.

Today, China has risen and replaced Japan as the leader of the Asian economy.

Compared with Japan, China has stronger advantages in terms of market size, economic depth, and policy independence.

Post a comment